|

Traditional Embroideries of Kutch

Kutch is world renowned for its mirrored embroideries. Most of these were traditionally stitched by village women, for themselves and their families, to create festivity, honor deities, or generate wealth. While embroideries contributed to the substantial economic exchange required for marriage and fulfilled other social obligations which required gifts, unlike most crafts, they were never commercial products.

Embroidery also communicates self and status. Differences in style create and maintain distinctions that identify community, sub-community, and social status within community. The "mirror work" of Kutch is really a myriad of styles, which present a richly textured map of regions and ethnic groups. Each style, a distinct combination of stitches, patterns and colors, and rules for using them, was shaped by historical, socio-economic and cultural factors. Traditional but never static, styles evolved over time, responding to prevailing trends. (for more information on Kutch embroideries, see Frater, Judy, "Embroidery: A Woman's History of Kutch," in The Arts of Kutch, Mumbai: Marg Publication, 2000.)

The Styles With Which We Work

Currently, KALA RAKSHA works with six distinct hand embroidery styles: the Sindh-Kutch regional styles of suf, khaarek, and paako, and the ethnic styles of Rabari, Garasia Jat, and Mutava.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Suf |

Khaarek |

Paako |

Rabari |

Jat |

Mutavas |

Patchwork |

|

|

Suf

Suf is a painstaking embroidery based on the triangle, called a "suf." Suf is counted on the warp and weft of the cloth in a surface satin stitch worked from the back. Motifs are never drawn. Each artisan imagines her design, then counts it out --in reverse! Skilled work thus requires an understanding of geometry and keen eyesight. A suf artisan displays virtuosity in detailing, filling symmetrical patterns with tiny triangles, and accent stitches. |

|

|

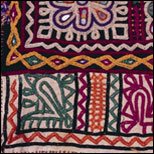

Khaarek

Khaarek is a geometric style also counted and precise. In this style, the artisan works out the structure of geometric patterns with an outline of black squares, then fills in the spaces with bands of satin stitching that are worked along warp and weft from the front. Khaarek embroidery fills the entire fabric. In older khaarek work, cross stitching was also used. |

|

|

Paako

Paako literally solid, is a tight square chain and double buttonhole stitch embroidery, often with black slanted satin stitch outlining. The motifs of paako, sketched in mud with needles, are primarily floral and generally arranged in symmetrical patterns. |

|

|

Ethnic styles express lifestyle. They are practiced by pastoralists whose heritage is rooted in community rather than land, and considered cultural property. |

|

|

Rabari

Rabari embroidery is unique to the nomadic Rabaris. Essential to Rabari embroidery is the use of mirrors in a variety of shapes. Rabaris outline patterns in chain stitch, then decorate them with a regular sequence of mirrors and accent stitches, in a regular sequence of colors. Rabaris also use decorative back stitching, called bakhiya, to decorate the seams of women's blouses and men's kediya/ jackets. The style, like Rabaris, is ever evolving, and in abstract motifs Rabari women depict their changing world. Contemporary bold mirrored stitching nearly replaced a repertoire of delicate stitches --which Kala Raksha revived. (for more information on Rabari embroidery see Frater, Judy, Threads of Identity: Embroidery and Adornment of the Nomadic Rabaris, Ahmedabad: Mapin, 1995.) |

|

|

Jat

Garasia Jat work similarly "belongs" specifically to Garasia Jats, Islamic pastoralists who originated outside of Kutch. Garasia women stitch an array of geometric patterns in counted work based on cross stitch studded with minute mirrors to completely fill the yokes of their churi, a long gown. This style, displaying comprehension of the structure of fabric, is unique in Kutch and Sindh. |

|

|

Mutava

The Mutavas are a small culturally unique group of Muslim herders who inhabit Banni, the desert grassland of northern Kutch. The exclusive Mutava style comprises minute renditions of local styles: paako, khaarek, haramji and Jat work, though these are known by different names. Specific patterns of each style, such as elongated hooked forms and fine back stitch outlining in paako, and an all-over grid in haramji, are also unique to Mutava work. Though technique varies, Mutava style is uniformly fine and geometric. |

|

|

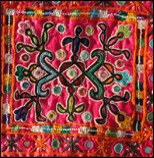

Patchwork and Appliqué

Patchwork and Appliqué

Patchwork and appliqué traditions exist among most communities. For many embroidery styles, master craftwork depends on keen eyesight. By middle age, women can no longer see as well and they naturally turn their skills and repertoire of patterns to patchwork, a tradition that was originally devised to make use of old fabrics.

Soon after Kala Raksha's inception, the Trust added patchwork to its line of products. Older artisans could thus join the cooperative. Women need not feel their earning days are numbered. The elder patch workers as well as younger embroiderers can earn.

|

|

|

|